The recorded history of Scriabin’s piano works has been blessed with a small number of performances with great provenance: those who knew the composer himself and whom he approved. Amongst these precious recordings there are such gems as the performance of Scriabin’s Sonata no. 4 by Samuil Feinberg, whose interpretation the composer particularly admired[1]. Scriabin’s colleague Alexander Goldenweiser performed and recorded several of the composer’s pieces, including a superlative performance of the piano solo part in Prometheus, conducted by Nikolai Golovanov.[2] Elena Beckmann-Scherbina, who premiered many of Scriabin’s works, recorded three pieces by the composer towards the end of her life; Preludes op. 15 No. 1 & 2 and the Valse op. 38.[3]

Whilst it is fortunate for Scriabinists that these recordings exist, it is equally unfortunate that other great pianists with similar provenance were never recorded, and thus now largely forgotten. Names that fall into such a category could include Mark Meichik, who premiered the composer’s fifth sonata, and Vsevolod Buyukli, who was Scriabin’s own favourite pianist. In the instance of Mark Meichik he did make several piano roll recordings, but these were either not issued, or likely those that were no longer survive. [4]

Amongst the ‘greatest Scriabinists never heard’, the Russian-American pianist Alexander Borovsky is most intriguing. Borovsky was born in Mitau, Latvia, on March 8, 1889 (March 18th Old Style), and died on April 27, 1968 in Waban, Massachusetts, USA. After studies with his mother, who herself had been a student of Safonoff, Borovsky went on to study both law and music. He graduated as a ‘free artist’ and won the Anton Rubinstein prize at St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1912, his principal teacher being Annette Essipoff (1851-1914). He also gained a first-class law degree in 1914 from the University of St Petersburg. On 5th October 1915, Borovsky would perform St Petersburg’s second memorial recital in honour of Scriabin, who had died six months earlier. This recital consisted entirely of Scriabin’s works, covering pieces spanning Scriabin’s entire compositional career, from the complete Op. 8 Etudes to the Ninth Sonata, op. 68.[5] The success of this recital would cause him to be hailed as one of the finest interpreters of Scriabin’s music of the day.

Borovsky continued to have a celebrated career as pedagogue and performer, in Europe, South America and Mexico before eventually settling in Boston, USA in 1941 – his brilliance can be heard in several recordings he made of repertoire ranging from Bach to Liszt and Rachmaninov. However, a notable absence is any audio recording of Scriabin’s works; there exist just two, commercially unavailable, piano rolls of three short Scriabin pieces: Prelude op.9 No.1 for left hand & Prelude op.15 No.2 (Duo-Art roll 6721) and the Impromptu op. 10 no. 2 (Duo-Art roll no. 6704)[6].

This lack of recordings has naturally led to the links between Borovsky and Scriabin’s music being overlooked. Fortunately, through material in the possession of the American pianist William Jones of Delmar, New York State USA, who was a student of Borovsky, fascinating connections between Borovsky and Scriabin’s music can now be rediscovered. William Jones’ unique resources include the vast unpublished memoirs of Borovsky, which contain first-hand accounts of Borovsky hearing Scriabin himself perform. [7]

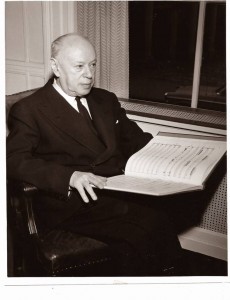

Alexander Borovsky, 1944 (Photo courtesy of http://alexanderkborovsky.blogspot.com)

Borovsky on Scriabin

Borovsky’s own interpretations of Scriabin impressed his contemporaries greatly, as will be discussed later. In view of this, it is a great loss that these performances were not recorded. In Borovsky’s memoirs, however, we are able to inherit something equally precious in descriptions of Scriabin’s own playing, which Borovsky heard at first-hand several times. He describes the difference in approach at the keyboard between Scriabin and Prokofiev; Prokofiev was a young admirer of Scriabin at the time. (NB- Small errors in Borovsky’s English have been allowed to stand)

‘Both Prokofiev and Scriabin were excellent pianists. Prokofiev was not interested in details, his playing was rather full of dash and sweeping audacity, but several details were not given proper attention or were even missed when he played his music and he did not care about the sounds which were mostly harsh and not cultivated. The same could be said of Scriabin who could also sacrifice the exactness and clarity of details for the spirit of his music, but here nothing of robustness or hard tone was admitted. Everything seemed to be ‘effleuré’ or delicately touched, very hard to be heard, so intimate and so fantastic and poetic. It was a different world from Prokofiev’s.’[8]

Borovsky gives a description of Scriabin’s own playing, with an anecdote recalling the audience’s confusion regarding Scriabin’s encores, in which he played some of his later compositions – many of the audience were not yet accustomed to the harmonic sonorities of these works.

‘I remember one symphonic concert on which Scriabin was soloist playing his own Piano Concerto (1897). As was customary in Russia he was asked to play an encore. He came to his piano and started to play one of his latest Poems. There on the stage three or four musicians of the orchestra were sitting close to composer, they probably did not have time to leave the stage because he came to play his encore almost immediately after playing with the orchestra. The ethereal qualities of his music did not allow him to exert any pressure on the keys of the piano, and it was hardly audible in the big hall what did he do at the piano.

When Scriabin finished to play the public was silent, and it was a moment of embarrassment which I felt as an offense to composer. At this moment the few musicians on the stage started to applaud and I saw Scriabin getting from his chair and making a bow to them. After this he sat and started to play another Poem, of this strange subtle weightlessness sonority. Again the audience did not react when he finished, but some youngsters in the hall clasped their hands to support the musicians on the stage, it was getting too comical, and happily the composer left the stage watched by the mass of indifferent or hostile people. I did not know then that the music of this composer will serve me as the greatest momentum for my success as a concert pianist in Russia.’[9]

The accounts given by Borovsky confirm other descriptions by Scriabin’s contemporaries, such as the London Times’ review of the composer’s playing with ‘its velvet touch, its exquisite precision of phrasing’[10] and others describing playing of ‘extraordinary inspiration and élan.”[11] Borovsky’s observation that Scriabin did not exert any pressure on the keys has similarities with Alexander Pasternak’s observation that Scriabin appeared to be “drawing the sound out of the instrument”, giving the impression that “his fingers were producing the sound without touching the keys, that he was (as it were) snatching them away from the keyboard and letting them flutter lightly over it.”[12]

On another occasion Borovsky writes:

Scriabin was also unparalleled in his piano playing. For all his last works, when he already pursued an independent path in art and achieved legendary status for his 9th and 10th Piano Sonatas; he was and stays unparalleled in his virtuosity; we will be deprived for centuries of the greatness of his piano performances. [13]

In his memoirs Borovsky speaks of his passion not only for Scriabin the pianist but also the composer:

“Scriabin was changing the patterns of his creation very rapidly. If he dwelled longer on his so called first period which is a sort of opigoneish [sic: epigonic] music to that of Chopin and later reminding of the music of Liszt, from the moment when he discarded these two sources of influence on him he opened the road to his independent ways of creation. And then with almost every new year, with every new piano sonata he was discovering new worlds each time. This ability to go from one unknown field to another with accompanying changes in the structure and in the sonorities was followed eagerly by the Russian musical youth for whom Scriabin soon was an idol, and ideal of modern composer, a genius of tremendous possibilities.”[14]

Finally, Borovsky recounts the moment the catastrophic news arrived to him of the premature death of the composer:

One morning in April my friend BASIL SACHAROFF, called me by phone, in a voice trembling with emotion. He informed me that Alexander Scriabin had died, at 43, of a cancerous carbuncle on the cheek. I could not believe such terrible news at first. Scriabin was something of a symbol for my generation of musicians in Russia; he had been making such remarkable progress, attaining new horizons with each work, filling us all with the expectation of great things as the result of his inspiration, and it seemed to us unbelievable and cruel that his mind should be extinguished at the very height of his creative powers. Nobody could grasp the immediate meaning of his tragic end, although I later thought I understood the reasons for it.”[15]

Borovsky’s Scriabin Memorial Concert 1915

The premature death of Scriabin served as an unintentional catalyst for Borovsky, still only in his twenties, to become one of the most important Scriabin interpreters in Russia at the time. (Borovsky’s initial piano training as a child already had connections to Scriabin, learning from his mother, who was herself a brilliant pianist and whose own teacher had been Vassily Safonov; the same as Scriabin). A number of commemorative recitals had been arranged to mark Scriabin’s death, of which Borovsky was chosen to perform one such recital in Saint-Petersburg.

“In the fall of the year of Scriabin’s death, 1915, the cities of St. Petersburg and Moscow organized commemorative festivals of his music, each city selecting three pianists to perform in its festival. Moscow was represented by Sergei Rachmaninoff, Mark Meichik, and Alexander Goldenweiser, while St. Petersburg, chose a man named Romanovsky, a Madame Barinova (if I recall the name correctly), and me, since ST. Petersburg was really my home city, even though I was then teaching in Moscow.”[16]

The preparation of this concert was one which must have been fraught with anxiety, given the hostile reaction to other Scriabin concerts at this time. Such was the devotion of Scriabinists to the composer’s own unique approach to the piano that even titans such as Rachmaninov could not escape criticism. Borovsky was disappointed in the reaction to Rachmaninov’s recitals particularly given the genorisity Rachmaninov had towards the Scriabin family, who were in financial difficulty at the time:

“At Scriabin’s open grave, Rachmaninoff vowed, and carried out the vow, to devote most of his forthcoming season to the music of Scriabin. He also gave all the proceeds from his numerous Scriabin recitals to the bereaved family, who were in financial distress at the time.”[17]

Borovsky himself was in attendance at Rachmaninov’s Scriabin memorial recital, criticising those who rebuked his performances:

Before leaving Moscow for my Scriabin program in St. Petersburg, I went to hear Rachmaninoff to play his music. Rachmaninoff could not put in his program any one of the latest works by Scriabin, as it was a world quite apart from his own, and he probably disliked all these strange compositions of the latest Scriabin. Therefore his program was filled only with the works belonging to the first period of Scriabin’s creation like Preludes, first Poems, some Studies and the cardinal number in the program was a Fantasy, Op 28, a long protracted composition without any plan or form, very repetitious and very noisy one. The composition alone of this program was disappointing to the addicts of Scriabin, and his touch which is so full of singing qualities was considered unsuitable to the subtleties of Scriabin’s world, and in the result the press was condemning Rachmaninoff for the shooting of guns salves upon the orchids. It was a sorry recompense to the artist for his noble gesture to prepare the whole recital program of his colleague who after all left the regions of music where both could be neighbors, and went into the fields of extreme modernism so foreign to Rachmaninoff. Especially wrong was this rebuttal to the artist after he had played with the orchestra the Concerto by Scriabin so wonderfully, so beautifully that for the first time he opened to the eyes and ears of the public what an incomparable pianist he was.[18]

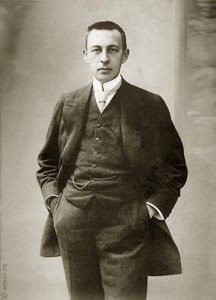

Rachmaninoff

Amongst those also in attendance at one of Rachmaninov’s Scriabin concerts was Prokofiev, who had himself told Borovsky that the tenor Alchevsky had to be restrained by the coat-tails from accosting Rachmaninov. He was heard shouting “Wait!” I’ll go and have it out with him.” Prokofiev also added his voice to the dissenters, “He [Rachmaninov] played the Sonata no. 5. When Scriabin had played this sonata everything seemed to be flying upward, with Rachmaninov all the notes stood firmly planted on the earth. There was some confusion amongst the Scriabinists in the hall.”[19] It is noteworthy that despite Prokofiev’s own evident admiration of Scriabin’s playing, Borovsky’s observations of Prokofiev as pianist suggest that Prokofiev did not attempt to emulate Scriabin’s approach to interpretation.

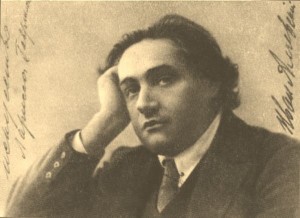

Prokofiev circa 1918

Borovsky’s anxiety over his own impending performance was heightened further by another scathing review of a Scriabin memorial recital in St Petersburg:

“Just before getting on the train at the Moscow railroad station, I bought a St. Petersburg newspaper and found in it a review of the Scriabin recital by the first of the three St. Petersburg pianists, Mr. Romanovsky. It was just as devastating as Rachmaninoff’s reception in Moscow, and I began to tremble at the thought of my upcoming trial, since it was beginning to appear that the memory of Scriabin’s inimitable piano technique precluded the possibility of anyone else’s success with his music.”[20]

Amongst the dissenters in Romanovsky’s concert was, again, none other than Prokofiev, who, a year later, wrote in his diary for 1916: “I am very glad I had hissed Romanovsky when he played it [Scriabin Sonata no. 4] in September: he had bashed his way through it then without the slightest understanding.”[21] Borovsky described a “personal alienation by the jealousy of the composer’s nearest friends and of his mistress, who never learned to tolerate hearing anyone praised for playing Scriabin, save Scriabin himself.”[22] Given such hostile conditions it is a testament to the brilliance of Borovsky as interpreter of Scriabin that his concert in St.Petersburg was an unquestioned success. Amongst the fervent applauders was Alchevsky, who had been so contemptuous at Rachmaninov’s recital.

“When I finally began my recital, I nearly lost control of myself, from the expectation of some awful disaster. I played the twelve studies of Op 8 with great tension and verve, and in the last study, a very pathetic and energetic piece of music, I played with real abandon, and was rewarded with the greatest ovation of my life! My artist room was filled at intermission with the most enthusiastic crowd (headed by the tenor Alchevsky) who were so happy to find someone who had played the music of their idol to suit their tastes.”[23]

Grigory Alchevsky- the tenor hugely approved of Borovsky as Scriabin interpreter.

In the second half of the same concert Borovsky had the audacity to perform the late works which Rachmaninoff had avoided. The overall success of the concert paved the way for Borovsky to become hailed as the “heir-interpreter of Scriabin’s works.”

“After the intermission I played some of Scriabin’s late works, for which I gained the approval of the critics, although the public did not react too favorably to this strange music. But the concert, all in all, was a real success, and I was proclaimed as the heir-interpreter of Scriabin’s works. I was then engaged to give another Scriabin recital on the anniversary of his death, and I did this for several years, until the Revolution disrupted the normal course of events.”[24]

Borovsky’s fame as an interpreter of Scriabin was soon not confined to Russia, as an article in the Musical Times of London, 1916, confirms. Referring to a new Scriabin Society in Moscow set up a year after the composer’s death, the young pianist is mentioned: “Moscow AS [Alexander Scriabin] Society recently founded. Addresses on various aspects of AS art have been given by MM Brando, Makovsky and Bryanchaninov, and the performance of the later works and also of some posthumous pieces has been in the hands of Borovsky, who is considered the finest exponent of Scriabin’s pianoforte music.”[25]

A year later, 1917, saw the founding of another Scriabin Society in New York by Alfred La Liberté. Scriabin’s widow, Tatyana Schloezer, wrote to La Liberté recommending Borovsky as a name to endorse the new venture: ‘I also propose the name of Alexander Borovsky, a young professor at the Conservatory of Moscow, who plays almost all the works of Scriabine, and has already acquired a great reputation as a pianist in Russia. Mr Borowsky is a member of the Scriabine Society’[26]

The Scriabin recitals given by Borovsky continued to make an impression, not least on the young Prokofiev. The reason Prokofiev recalled in his diary of 1916 being glad he had hissed Romanovsky’s fourth sonata a year earlier was his hearing of Borovsky’s own exceptional interpretation at his latest Scriabin recital. Prokofiev wrote “Borovsky played truly wonderfully today, especially Scriabin’s fourth sonata. I am very glad I had hissed Romanovsky when his played it…”[27] Prokofiev’s descriptions of Borovsky’s playing demonstrated the pianist’s ability to give clarity to the complexities of the late works. Again in 1916 he wrote, “Scriabin died a year ago today. Borovsky played a recital of his works with his customary excellence, the Sixth Sonata being particularly fine. I have not hitherto known this sonata very well, but this time it gave me tremendous pleasure.”[28]

Whereas Borovsky had initially been one of the first to perform the later works of Scriabin, unlike Rachmaninov, over time he himself began to favour the later works less, doubting the staying power of the music and the works’ structural integrity:

“Due to the great popularity of these recitals, which were sold out two or three days after the tickets went on sale, I naturally developed a large Scriabin repertoire, including seven of his ten sonatas. But I found that I, too, could not long endure the amorphous quality of his last works, the ascetic lack of accompanying voices, the countless repetition of certain formulas, and the complete lack of formal organization. When Scriabin himself played his music, the unexpected mannerisms and effusive exaggerations were suggestive of some spiritual inspiration, which impressed his listeners. But as I worked over this music for a long period of time, all its defects came out in the open, and I realized that I was more satisfied by the music which better stands the test of times and is not so distinctly “fin-de-siecle.”[29]

Perhaps this loss of conviction regarding the works had, for a time, some detrimental effect on his own performances. Whereas Prokofiev had praised Borovsky’s playing before, a later recital left a markedly different impression, both of Borovsky’s playing and perhaps Prokofiev’s own diminishing regard for Scriabin’s music. “On the 14th I attended a recital of works by Scriabin marking the second anniversary of his death. And it was a strange experience… Scriabin’s preludes seemed to me so neutral, so tame and irrelevant…”[30] In particular reference to the seventh and ninth sonatas Prokofiev added, “I did not care much for Borovsky’s interpretation either: it was cold and superficial.”[31]

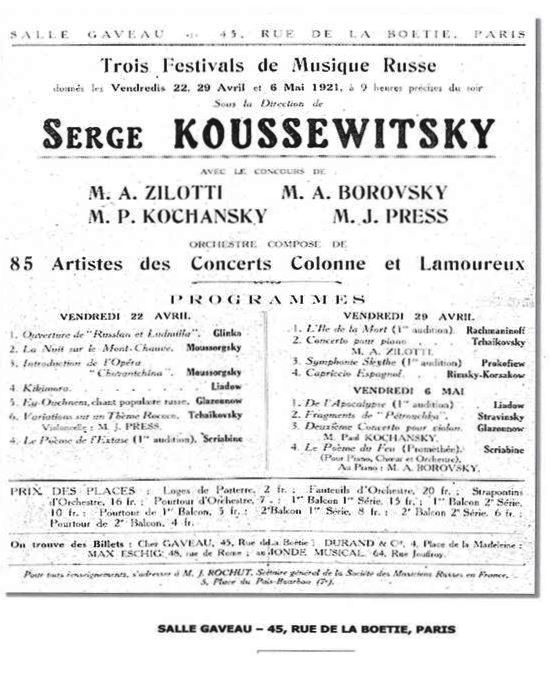

Despite Prokofiev’s reservations, Borovsky continued to be one of the most celebrated Scriabinists, as is evident by his being asked to perform the solo part of Prometheus under the baton of Sergei Koussevitsky, who was himself a great champion of Scriabin’s music and with whom Scriabin had performed his own piano concerto some years earlier. This concert took place in Paris 1921, and later with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1923, still under the baton of Koussevitsky.

Programme announcing Borovsky’s performance of the solo part of Prometheus, conducted by Koussevitsky.

It is hoped this article will further the knowledge of the important links between Borovsky and Scriabin, encouraging recognition of the historical importance Borovsky’s piano roll performances of Scriabin, which we also hope may lead to their being eventually made available to the public in digital recordings.

Acknowledgements: I am sincerely grateful to William Jones for contacting the Scriabin Association to share his unique documents that have made detailing the links between Borovsky and Scriabin possible. I am also grateful to Simon Nicholls whose own advice, proof-reading and thorough knowledge of Scriabin has been invaluable.

Darren Leaper 2016.

[1] Feinberg also left a substantial recorded legacy of Scriabin’s works, including most of the Mazurkas and the concerto.

[2] Available on: ‘The Art of Nikolai Golovanov, Vol. 1: Scriabin: Piano Concerto / Poem of Ecstasy / Prometheus, the Poem of Fire’ ASIN: B00008EP3H or The Art of Nikolai Golovanov: Scriabin – The Poem of Ecstasy & The Poem of Fire “Prometheus” Music Online

[3] Available on Russian Piano School vol. 11- Melodia 74321332092. Her performance of the Valse op. 38 is also available to listen at http://classical-music-online.net/en/production/285

[4] A piano-roll recording of Meichik playing the Scriabin 5th sonata was made, but it is likely no surviving rolls exist, or it was never issued. He also recorded:

- Etude op 8 no. 8 for Welte-Mignon

- Etude op. 8 no.12 for Duca

- Poemes op. 32 no.1 & 2 for Duca,

- Poeme Tragique for Welte-Mignon

- Prelude op 37 no.1 for Welte-Mignon and Duca

- Prelude op. 48 no 2 for Welte-Mignon

(Information from: Daniel Bosshard, Thematisch-chronologisches Katalog der musikalischen Werke von Alexander Skrjabin, Trais Giats, Ardez, 2002.)

If anyone knows the whereabouts of any of the above please contact the Scriabin Association.

[5] See: Charles Barber, Lost in the Stars: The Forgotten Musical Life of Alexader Siloti Scarecrow Press, 2002 pg. 332

[6] It is hoped these may soon be available to hear. The Scriabin Association will inform members should this be the case.

[7] William Jones’ own dedicated site to Alexander Borovsky can be seen at http://alexanderkborovsky.blogspot.co.uk .

[8] Op. cit

[9] Op. cit.

[10] M.Scriabin At Queen’s Hall. First appearance in England The Times, March 16th 1914

[11] Reminiscence of Ossovsky quoted in Rudakova & Kandinsky – pg. 114, op.cit.

[12] A Pasternak – Scriabin summer 1903 and after, The Musical Times vol 113 pp. 1173-1174

[13] This extract was provided by William Jones from a lecture recital given by Borovsky in 1933 at the Russian Conservatory in Paris.

[14] Borovsky’s unpublished memoirs, information provided by William Jones.

[15] Op. cit

[16] Op. cit.

[17] Op. cit

[18] Op. cit

[19] Prokofiev, Autobiography, Articles, Reminiscences, Moscow, pg. 41

[20] Borovsky – Op. cit.

[21] Sergei Prokofiev, Diaries 1915-1921 Behind the Mask- translated by Anthony Phillips. Faber & Faber (2006) pg. 85

[22] Borovsky – Op. cit.

[23] Op. cit.

[24] Op. cit.

[25] Musical Times of London-August 1916

[26] Musical Courier, October 18th, 1917 – It is also of interest that this published letter is signed by Tatyana Schloezer as T. Scriabine. Officially she was not allowed to use this surname given she was never actually married to Scriabin; he and his first wife were never divorced. Tatyana’s children from Scriabin were however given permission to use the surname.

[27] Sergei Prokofiev, Diaries 1915-1921 Behind the Mask- translated by Anthony Phillips. Faber & Faber (2006) pg. 85

[28] Prokofiev diaries, op. cit. pg. 123

[29] Borovsky – Op. cit.

[30] Op. cit pg. 189-190

[31] Op. cit.