Abstract

The Eighth Sonata, the longest of Scriabin’s one-movement sonatas, was the last of the cycle of ten to be finished. It differs greatly from the other late sonatas in its extensive, apparently discursive form and generally more subdued expressive register, yet it has always fascinated players and listeners. The present study attempts to show that the linked qualities of symmetry and repetition which mark out the Eighth are a logical culmination of Scriabin’s developing and original treatment of sonata form from his earliest works; to suggest why he placed it in the position he did, instead of at the end of the cycle; and to investigate the deep logic of the form of the work. The sonata lacks the numerous subjective performance directions of the other late works, with a few important exceptions, but Scriabin made some significant comments about it. The content of the work is investigated with reference to those comments. Valentina Rubtsova has stated that the last sonatas were regarded by the composer as preliminary studies for the Mystery.[1] Concepts in Scriabin’s libretto for the Preliminary Action, the ‘preparation’ for the Mystery, and relevant earlier writings are also drawn into comparison. Commentaries from 1915 to 2016 are drawn into the discussion, as well as twentieth-century literary, scientific-philosophical and musical references.

A version of this article was published, in Russian translation, in A. N. Skryabin i sovremennost’: zhizn’ posle zhizni (Skryabin and the present day: life after life), edited by Alexander Serafimovich Skryabin, celebrating the 25th anniversary of the founding of the A. N. Skryabin Foundation, Moscow. The Centre for Humanitarian Initiatives, Moscow–St. Petersburg, 2016.

The development of form in Scriabin

Scriabin’s engagement with sonata form was life-long: one of his earliest existing manuscripts is the Sonate-Fantaisie in G sharp minor, finished in August 1886 at the age of fifteen. Its form anticipates to some extent the pattern of the Fourth and Fifth Sonatas: it begins with a slow introduction whose recapitulation (fragmentary in this case, a mere hint) frames a fast movement. Between this youthful work and the Eighth Sonata, the last of Scriabin’s ten sonatas to be finished despite its numbering, stand not only the other nine sonatas and the five symphonic works of the canon, but also an incomplete sonata movement in C sharp minor begun in September 1887 and a sonata in E flat minor dating from 1887–1889. The first movement of the latter work, expanded and corrected, became the Allegro appassionato op. 4 in 1882, and the Allegro appassionato is not the only extended movement by Skryabin in sonata form which lacks the title Sonata: further examples are the Fantaisie op 28 and the Poème-Nocturne op. 61.

Scriabin has been criticised for holding to the traditional form throughout the transformation of his musical language: Sabaneyev referred to the ‘schematicism’ of his later works, and the German critic Carl Dahlhaus accused him of taking over the traditional form ‘gehorsam und unkritisch’ [obediently and uncritically].[2] But from the beginning there were original elements in Scriabin’s handling of form. The fragmentary recall of the slow introduction in the G sharp minor Sonate-Fantaisie, forming the ‘frame’ or ‘bracket’ which becomes so important to Scriabin later, has been mentioned. In the First Sonata, op. 6, completed in 1892, the form is modified and interrupted to expressive purpose, to express Scriabin’s despair at the hand injury he thought was going to be permanent: in the finale, exactly where our expectation is that the second subject will return triumphantly in the home key, the movement we have taken to be the finale breaks off, a fragment of the second subject is heard in the minor and a remorseless funeral march ensues. This ‘meaningful contradiction […] of what we have been led to expect’ was defined by Hans Keller as constituting ‘the language of music’, the method by which ‘musical understanding’ is communicated, and Keller’s simplest example of it was the interrupted cadence.[3] Here Scriabin achieves a harrowing emotional effect by working on the level of formal expectations. From this point on Scriabin is able to use the modification of form as an expressive element in his music.

The treatment of form in Scriabin’s earlier symphonies is also highly original. Of the six movements in the First Symphony, the first and last frame a conventional four-movement structure: Allegro drammatico, Lento, Vivace, Allegro. The recapitulation in the finale of ideas from the first movement provides an element of symmetry to the framing, and the addition to the finale of words, which are heard over the first movement’s ideas and the second movement’s exalted theme, marked at its first appearance Più,[4] reveals that the first movement’s enchanted world and the exaltation of the ‘Più’ theme are to be attributed to the influence of Art, and of Music in particular, the ‘wondrous image of the Divine’ (words from the choral movement).

In the Third Symphony (Divine Poem) the sonata form of the first movement is extended by a second development section following the recapitulation (b. 745, number 43 in the Belaieff score). This second development section also provides another example of an element of symmetry in the movement, in addition to the normal correspondence of exposition and recapitulation.

It is in the later music of Scriabin that we are most conscious of his careful calculations concerning form, though this was most probably his method throughout life. During the composition of the Poem of Ecstasy he wrote to his life-partner Tat’yana Schloezer:

For the thousandth time I am pondering the plan of my composition. […] Up till now everything is only schemes and more schemes! […] For the enormous structure that I wish to raise a perfect harmony of the sections and a firm basis are necessary.[5]

During the composition of the Seventh Sonata he said to Sabaneyev: ‘It is necessary that a form like a sphere, perfect as a crystal, be obtained.’[6]

In these quotations the importance of proportion and symmetry is very marked. Scriabin was to move closer and closer to this ideal.

In writing of Scriabin’s later music, both the Russian writer of the Soviet period Sergei Pavchinsky and, it seems independently, the German writer Gottfried Eberle have proposed a form on two layers, whereby the conventional sonata form is overlaid with another tendency.[7] In the Fifth Sonata, as in the Poem of Ecstasy to which it is closely related, the overlaid tendency is an upward spiral, processes of elation and languor alternating and rising in intensity (and in tonality) until the final ecstatic peroration. In this sonata, too, we have a ‘frame’, and a unique one: the opening ‘upflight’ which corresponds to Scriabin’s ‘motto’: ‘I call you to life, hidden strivings!’ and which recurs periodically at formal divisions and at the end. The repetitions at ever-higher pitches of the ‘slow introduction’ material and of the ‘upflight’ undergo at times ingenious transformation (b. 247–270).

An uninterrupted rise to an ecstatic conclusion, irrespective of the formal process, is achieved in the Seventh Sonata by means of another transformation: a heightened and re-scored recapitulation. The amplified sonority and re-arranged layers of the return to the beginning ensure that, far from showing a drop in tension, this moment is one of the most thrilling in the work. The recapitulation of the Ninth Sonata is equally startling, with the doubling of the speed of the opening figuration and the hugely amplified instrumental writing. In the American expression, ‘all Hell breaks loose’ at this point. Scriabin does not adopt the method of Chopin in the B minor piano sonata (op. 58) and the cello sonata (op. 65), of avoiding a drop in tension by eliding the beginning of the recapitulation, so that the music does not settle until the second subject: the clarity of his formal periods is too important to him.

The Eighth Sonata presents the player and the listener with a fascinating enigma: no such dramatic ascent as in the Seventh Sonata, no such cruel climax as in the Ninth (alla Marcia), and yet the work is immediately compelling, hypnotic even. This is the longest of all the one-movement sonatas, and the form of the Eighth is at first puzzling to the listener and perhaps to the player studying the work, owing to the many repetitions of the material and the lack of obvious climactic points. E. P. Meskhishvili wrote of an element of ‘mosaic construction’.[8] But the sonata represents the culmination of the process of an original, modificatory treatment of sonata form which Scriabin seems to have had in his mind from early on, as well as the transformation of harmonic language. To Elena Gnesina, at the age of eighteen, he said:

I imagine […] some sort of music, not at all like what is being created now. In it will be, as it were, the same elements as in the music of the present time – melody, harmony, but all this will somehow be completely different![9]

This statement is complemented by a remark in a letter to Natalya Sekerina written from Samara in 1893:

I am making calculations in relation to musical forms, and here is the sort of thing: this morning I was reading a splendid work on the flora of our planet and of the relation of tropical forms to the forms of other latitudes. […] Taking the forms of our contemporary music as the forms of the middle latitudes in relation to the musical equator, I am making a comparison of these forms to the ideal ones (that is, to the most developed and the broadest) and am comparing it to the other, already discovered relation between tropical forms and those of the middle latitudes.[10]

In other words, however complex and luxuriant in proportion the form becomes, it will obey certain basic principles, just as the bewildering luxuriance of tropical plants may obscure their inner structural relationship with those of the zone covered by the middle latitudes. If the Eighth Sonata is the final one in Scriabin’s oeuvre, it is only reasonable that we should expect its form to be the most ‘ideal’ – the most developed and the broadest – but that we should seek its basic formal tendencies, with whatever they may be overlaid, in the sonata principle (the classical sonata form corresponding to the ‘middle latitudes’). First, though, a few speculations as to why the Eighth Sonata, composed last (and intended to be the last sonata Scriabin would write – he was intending to turn thereafter to the Preliminary Action and then to the Mystery) is known not as the Tenth but as the Eighth – why Scriabin placed it in this position.

Numbering of the late sonatas

It is clear that Scriabin made choices concerning the numbering of his last five sonatas. The Sixth was written after the Seventh (both 1911-12, Kashiry –Beatenberg and Moscow), and though numbers Eight, Nine and Ten were worked on more or less simultaneously and may be regarded as a trilogy, the Ninth was started first (Beatenberg, Autumn 1911), not being finished till summer 1913 in Moscow; the Tenth was worked on in Moscow in the winter of 1912–13 and finished before the Eighth, at the latest in early June, and the Eighth was begun in winter 1912/13 and finished in early summer 1913. The three sonatas were sent simultaneously to the publisher.[11]

If we follow the numbers 5–7 and 9–10 we find a simple alternation of light and dark. But the Eighth Sonata does not fit into this pattern, and is harder to categorise in this way: Pavchinsky found in it ‘something mysterious and nocturnal’;[12] for the early American biographer Alfred J. Swan it was ‘bright and exuberant, […] a divine azure vault, the happiest and most careless of inspirations.’[13] The numerical symbolism of H.P. Blavatsky, whose Secret Doctrine was Scriabin’s constant reading, may give us a clue to Scriabin’s choice of numbering, and to the symbolism of the sonatas – remembering especially the remark of V.V. Rubtsova that the late piano sonatas were conceived as ‘preliminary studies’ for the Мystery.[14] Seven, for Blavatsky the ‘Septenary’, was fundamental to the cosmic cycle, ‘the seven earths and the seven races’.[15] It is natural for it to be associated with the sonata which, according to Scriabin, was ‘completely close to the Mystery’[16] – the Mystery which was to sum up the cosmic cycle which was, according to Scriabin’s thinking, coming to an end. The number eight is associated by Blavatsky with ‘the eternal and spiral motion of cycles’, and she associates the numeral 8 with the symbol ∞ of infinity. (We may note that the first of two sketches by Scriabin included in the 1919 publication of his writings, Russkie propilei, is based on such a figure).[17] Scriabin stated that the Eighth Sonata was ‘by mood […] close to the Seventh […] only it is more all in a dance’ (an important clue for the interpreter, not always realised in performance).[18] Once again, we may think of the concept of the revolving cosmic cycle, and the typical circular dances of Scriabin, both associated with the Mystery.[19] Nine, Blavatsky states, symbolises ‘our earth animated by a bad or evil spirit’[20] (cf. Scriabin’s remark to Sabaneyev: ‘It is entirely mischievous, this Ninth sonata, in it is some kind of evil spirit’ [Sabaneyev’s emphases].[21]) Ten, according to Blavatsky, ‘brings all […] to unity, and ends the Pythagorean table.’ For Scriabin the Tenth Sonata, the last in the canon, was ‘genuine dissolution in nature. This is also the Mystery’.[22] Tamara Levaya writes of the Tenth as the ‘companion and antipode’ of the Ninth and as representing a concept of the Mystery of a character ‘of full mutual inter-dissolution with Nature and the Cosmos.’[23] Thus the last four sonatas are arranged as two pairs: Seven and Eight are closely linked by their philosophical subject matter but differ greatly in approach, whereas Nine and Ten are antipodes. The negative pole, represented by the Ninth, is enclosed by the ‘mysterial’ sonatas.

Harmony, Thematic Material and Content of the Eighth Sonata

The Eighth Sonata may be said to contain the widest range of harmonic vocabulary of any of the late sonatas, from the distantly extra-tonal[24] opening to the radiant Promethean harmony of bars 46–56, which culminate on a straightforward seventh chord on A. Scriabin spoke of the ‘thematic counterpoints in the introduction of the Eighth Sonata’ as showing ‘complete reconciliation’.[25] This opening certainly shows Scriabin’s extra-tonal style at its farthest reach, apart from some passages in the preludes op. 74 and the sketches for the Preliminary Action. In this style, where harmony and melody are one and the harmonic relations are complex and oblique, we do not feel, as in the music of Bach which Scriabin evoked as a comparison, a strong directionality, but rather a dynamic stasis. This music expresses Scriabin’s concept of all-unity; all the thematic elements of the sonata are completely reconciled in a near-frictionless combination.[26]

The article by Evgenyi Mikhailov already cited characterises this introduction with the expression: ‘a state of “non-separation before creation”’.[27] This expression recalls the ‘concreteness in unity’ which Scriabin illustrated musically for the philosopher Fokht in the third of their conversations in 1910, and which Fokht recounted much later in a typescript not published until 1994.[28] Earlier still, in the notebook of 1905–1906, Scriabin wrote:

The universe is a unity, the connection of the processes co-existing in it. In its unity it is free. It exists in itself and through itself. It is (has within it) the possibility of everything, and everything.[29]

This introduction, with all the thematic potentialities combined in balanced stillness, is a musical analogue of the concept Scriabin set down in his notebook – at a time when his own musical language was developing towards being able to express this state.

The character of the thematic material also needs examination: the nature of the themes, as well as the form, determines the character of the work, and both have to be in harmony with each other.[30]

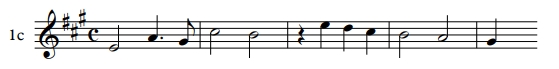

Four themes are stated in the introduction. The first (mus.ex.1a) consists of two elements: one rising in a zigzag and the other falling chromatically.

This theme has close connections with the theme of self-assertion in the Poem of Ecstasy and the fugue theme of the final chorus in the First Symphony Slava iskusstvu [‘Glory to Art’] (1b, 1c), both of which show similar features;[31] slow and abstracted here, it appears in the last part of the exposition and, following Scriabin’s description below, I give it the name ‘theme of dissolution’.

The second (mus. ex. 2a), which appears while the first is being completed, is the only theme which shows a completed arching gesture expressing a romantic pathos. It reappears (mus. ex. 2b) marked ‘Tragique’, one of only three French performance directions in the work; we may label it the tragic theme.

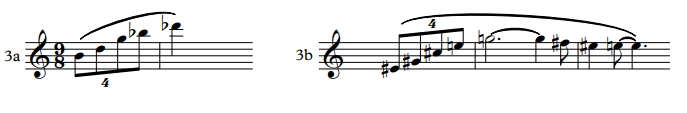

The third theme (mus.ex.3a), rising through a diminished tenth (Scriabin’s enharmonic spelling of a major ninth), Pavchinsky labelled ‘the motive of languor’. It is stated three times, acquiring a new extension at both repetitions. At the third appearance it grows a tail which repeats itself and becomes important in the development section.

The outline of this repeated tail (3c) gives rise to the theme which appears in its fullest form at the end of the exposition (3d) and leads to the development – I give this theme the name ‘connecting theme’ because of this function.

The fourth (mus. ex. 4a) is the simplest – a rising second. Like the rising semitone of Vers la flamme op. 72, it has the quality of a primal impulse. Stated three times in the introduction, it grows into the principal theme of the Allegro agitato (mus. ex. 4b), with which the cascading fourths which are a feature of the Eighth Sonata are associated.[32] They constitute, not a simple descent, but a double curve, representing a hint of a whirlwind or eddy. It is tempting, and may be helpful in interpretation, to attach to them a phrase from Scriabin’s notebook of 1904–1905, ‘the trembling of life’.[33]

With the exception of the tragic theme (ex.2b) which appears in the position of the second subject, the themes in Sonata No. 8 are unusually abstract and shorn of personal expressive value. This is certainly as intentional as the contrast between lyrical theme and aphoristic motif in the Sixth Sonata. The repeated ‘tail’ of theme 3 (mus. ex. 3c) and the up-and-down of the connecting theme 3d, closely related to it, call to mind the movement of branches in the wind or plants in the water. The first phrase of the principal theme of the allegro agitato (ex. 4b), developed from the primal motif of a rising second stated in the introduction (4a), describes a perfect fifth – in outline it is essentially a Naturthema. The detail of this first phrase, set in triads, like the prestissimo volando theme of the Fourth Sonata, gives us the exhilaration of arising life:[34] two pulsing rising seconds, and a third rise which rests for a moment on a syncopated raised fourth before arriving at the fifth. The corresponding phrase at bar 32-34, significantly, ends with a semitone drop (marked ‘a’), again syncopated (4c): an anticipation of the downward curve of the ‘tragic theme’, as if the beginning of life contained the seeds of its ending.

The forceful, fully expressed form of the ‘tragic theme’ appears at bar 88, marked ‘Tragique’, in the position of second subject. Of this passage Scriabin remarked:

‘But here I have a change of mood in the course of one phrase […].Tragic… but out of it is born such dissolution…suddenly…’[35]

Scriabin’s second subjects were highly significant from the beginning: we may think of the uplift of the second subject in the First Sonata or the consolation of the second subject in the Fantaisie. Later, perhaps under the influence of the gendering of themes in the writing of A. B. Marx,[36] they came strongly to represent a feminine principle: the second subject in the Sixth Sonata is the only lyrical theme in a work whose ideas are markedly laconic. In the Ninth sonata the second theme represents a ‘slumbering sanctuary’, in Scriabin’s own words.[37] Both these themes undergo transformation, as does the second subject of the Tenth, which reappears as a blazing vision of the sun. In the Eighth the role of the second subject undergoes further modification: rather than being acted upon, as in the earlier sonatas, it has pivotal significance in the musical narrative.

Stefanie Huei-Ling Seah, following a hint from Faubion Bowers on the associations in the Russian language to the word ‘tragic’, suggests that in this moment ‘the major tenth ascent may be understood as being heroic prior to the despair of the semitone descent from the G apex to the G flat […]’[38] This suggestion we may associate with the remarks of Valentina Rubtsova on the Poème tragique, op. 34, which she associates with the ‘self-assertion’ of the Poème op. 32 no. 2. The descending phrases of the middle section of the Poème tragique she connects with the ‘theme of protest’ in the Poem of Ecstasy; this section, with its downward-leaping phrases from the trombones, is marked tragico.[39] In other words, this is a matter of a heroic protest: in a scenario familiar from the Poem of Ecstasy, the will has met with an obstacle to its progress. But here the following events are very different from the struggle which ensues in the Poem of Ecstasy: to repeat the quotation from Scriabin himself, ‘from it is born such dissolution …immediately’.[40] Struggle is not Scriabin’s preoccupation in this piece, though we may find elements of opposition in the development section. The two sections of enchanted tranquillity (Meno vivo, b.173-185 and 242–263), surrounded by agitated moods, bring to mind a stanza from the Preliminary Action:

Only through the foam of sensuality is it possible to penetrate

Into that secret realm where the treasures of the soul are

Where, having grown sick of the predilections of the agitated soul

The holy one is blissful in radiant stillness. [41]

Viktor Del’son suggested that the Sixth and Eighth Sonatas shared features of

strongly abstracted expressions of the elemental forces of nature, a reflection of the world surrounding us as one of the manifestations of the cosmos, of the All. [42]

Pavchinsky associated the ‘tragic theme’ in its situation amongst the other more abstract themes with the idea of

[…] a hero amid the agitated night before a thunderstorm, with its gusts of wind and threatening indistinct sounds carried towards us.[43]

But, bearing in mind the early evidence of Gunst that

[…] the music of Scriabin, being the embodiment of a certain experience, […] never by any means contains within itself any kind of hint of programmicity in the generally accepted meaning of this word […][44]

it may be preferred to look at the content of the exposition in the Eighth Sonata in a more abstract way, as the emergence of life, beginning agitatedly (b.21–25), gaining momentum and reaching its aim of joy at b. 46 (joyeux); the chain of intervals in the theme of dissolution is extended to a full octave at b. 52–55. (Mus. ex. 5; Pavchinsky gave this passage the name ‘theme of upflight’.)

At bar 88 the stage of consciousness and protest is reached[45] and the final stage of dissolution or dematerialisation, like that which ends the Preliminary Action,[46] ensues with one of Scriabin’s finest passages of twittering and flight, the themes 1, 3 and 2 without its rising first member all being present (b. 96–117). All this may be regarded as forming a final group in the exposition, and it is theme 2 in its shortened aspect which has the last word, here as at the conclusion of the sonata. (Presenting only the downward element of theme 2, omitting what Seah calls its ‘heroic’ aspect, robs it of its pathos. Scriabin knew the value of adding or subtracting a few notes at the beginning of a theme: the Poème-Nocturne’s first theme lacked its anacrusis in manuscript, as well as in the list of ‘themes for sonatas’ compiled by Scriabin,[47] but now that anacrusis seems utterly indispensable to the enigmatic character of the music. The ‘theme of will’ in the Poem of Ecstasy is first stated early in the work without its first three rising notes.) The pattern of events in the exposition is repeated in the recapitulation, while the coda may be said to concentrate on the stage of dematerialisation, which happens twice in quick succession – corresponding, perhaps, to Blavatsky’s theory of repeated cycles of existence and to Scriabin’s theory that time would speed up as the Mystery approached.[48]

Scriabin, time and the formal plan of the Eighth Sonata

Scriabin expressed to Sabaneev his belief that music could ‘enchant time’.[49] He expressed himself similarly concerning the Prelude op. 74 no. 2, which shows a repeating, circular form, ‘as if it sounds for ever’. [50] The Two Dances, op. 73, show the same tendency, which may have started with the Fifth Sonata – but perhaps even earlier, with the ‘framed’ structure of the youthful Sonata-Fantasy. The literary Poem of Ecstasy,[51] as well as Scriabin’s belief in repeated manvataras,[52] systematises this circular or spiralling principle, as does the symphonic poem. The sensation of listening to, for example, a Beethoven symphony, or to the first movement of Chopin’s B minor sonata (cited above), is a linear one of great purposefulness, and Chopin’s formal innovation (also described above) increases this linearity. Scriabin’s view of time and space, though, was a very different one; he regarded the present moment as a border between two non-existent worlds: the past, which has gone, and the present which has not yet come.[53]

A part of Scriabin’s ideas of time may have been influenced by the writing of Henri Bergson. Bergson’s Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience first appeared in 1889. We do not possess evidence that Scriabin read this book, though we do know that he studied a paper by Bergson given at the Geneva Congress of Philosophy in 1904. Boris Pasternak recounts in Safe Conduct the importance of Bergson amongst students at Moscow University in the early years of the century.[54]

Bergson’s Essai contains a famous account of the way that humans mentally ‘construct’ the passage of time:

nous projetons le temps dans l’espace, nous exprimons la durée en étendue, et la succession prend pour nous la forme d’une ligne continue ou d’une chaine […].[55] We project time into space, we express duration in length, and succession takes on for us the form of a continuous line or of a chain…

Bergson’s passage refers to the way we perceive a succession of notes as a coherent melody. The same process applies in apprehending the form of a piece of music. The English novelist E. M. Forster wrote about literary form in visual-geometrical terms, similar to those used by Scriabin; and he had this to say about musical form:

Is there any effect in novels comparable to the effect of [Beethoven’s] Fifth Symphony as a whole, where, when the orchestra stops, we hear something that has never actually been played? […] this new thing is the symphony as a whole […].[56]

It is through memory that we perceive form,[57] and memory is conditioned by time. The form itself, though, is perceivable as a static entity. It is this static aspect, ‘outside time and space’, to which Scriabin moves ever more closely, both in his musical language[58] and in the formal process.[59]

Although he worked at the piano while composing, Scriabin disapproved of improvisation: ‘This is not art, because it cannot be formed […]’[60] Here we may turn to another literary figure, T. S. Eliot, for illustration and clarification:

Words move, music moves

Only in time; but that which is only living

Can only die. […]Only by the form, the pattern,

Can words or music reach the stillness […].

And the end and the beginning were always there

Before the beginning and after the end.

And all is always now. […][61]

Scriabin’s ‘pattern’ has been accounted for in different ways, most notably by Pavchinsky [62] and the French writer Manfred Kelkel.[63] Both draw attention to the high degree of symmetry in Scriabin’s design; Kelkel writes:

Toute la 8ème sonate est structurée des débuts aux extrêmes (Introduction – Coda) comme un miroir à doubles facettes […][64] The whole eighth sonata is structured from the beginning to the extremities (Introduction–Coda) like a mirror with double facets…

Of the outermost element, the thematic correspondence of the slow introduction with the accelerating, dancing coda, Pavchinsky writes:

the most extended arc of the form on the second level [see above] is represented by the co-relation of introduction and coda, where the variation of the fundamental theme translates the images of the introduction from their ‘languorous’ reflection and enigmatic character into the sphere of flight and of pantheistic dissolution.[65]

The correspondence of exposition and reprise, normal in a sonata, needs no comment. It is in the development section that opinions vary. And it is important to stress that it may not be possible to arrive at a single conclusive answer. Musical functions remain fluid and multivalent, susceptible to varying interpretations – each of which may have something to contribute.

Pavchinsky, whose analysis both of harmony and form is based on traditional functions, finds within the development section two sections (b.174–213 and 242–291[66]) which are in the relationship of exposition and reprise – a ‘sonata without a development’[67] within a sonata. Kelkel, basing his analysis on the metrotectonics of Georgii Konyus, proposes three sections: b.118–173, 174–263, 264–319.[68] My own analysis is based on the experience of learning to play this enormous continuous movement, looking within it for meaningful correspondences between sections which aid memory, comprehension and orientation. Taking the hint from Pavchinsky’s reference to an arch, I propose that what Pavchinsky calls the second level of the form – the background level – is a principle of symmetry approaching that of a great arch. We have established that the outmost layer is formed by the introduction (1–21) and the coda (429–499), which are themselves in the relation of exposition and transformed recapitulation. The coda is itself symmetrically built: b. 429-448 are concerned with the ‘theme of tragedy’ and 449–464 with the ‘theme of dissolution’. These two sections are repeated in b.465–482 (transposed up an augmented fourth) and 483–494 (at the original tonality, but with the two upper voices reversed in position.) The last five bars restate the ‘theme of tragedy’ without its upward-leaping member, as at the end of the exposition (114–118) and of the recapitulation (408–416). Once again the repetition is threefold. The second layer in the arch is formed by the exposition and recapitulation (22–121, 320–428) and the third by sections 2 and 4 of the development (158–213, 226–291). (Diagram 1).

Diagram 2 shows the structure of the development. There are five sections. The first is symmetrical in itself: an eighteen-bar structure built on the first theme followed by the ‘theme of tragedy’ is repeated one tone lower. The second and fourth sections match and form a symmetrical pair around a twelve-bar connection.; section 4 is transposed up a minor third from section 2. 2i is built from the tragic theme in combination with theme 3 and the connecting-theme. In 4i these elements are joined by the ‘trembling of life’, making this one of the most complex contrapuntal textures in the work. 2ii and 4ii (Meno vivo) are based on theme 4 combined with a calmer version of the descending fourths, (in quintuplets and single notes). 4ii is extended via a three-fold repetition of the end of the theme. 2iii and 4iii (Tragique. Molto più vivo) are built on the ‘theme of tragedy’ and the connecting-theme.

The connecting sections, 3 and 5 (in dance-flight mode) start very similarly. 5i and ii are again a minor third higher than 3i and ii. In 3ii and iii the ‘twittering’ alternates with ‘calls’ (the three rising notes of the ‘theme of tragedy’) and with the falling fourths from the ‘trembling of life’. 5ii and iii reproduce the music of dissolution near the end of the exposition (from b.96), which will be heard again from b. 394 near the end of the recapitulation. 3ii and iii hint at this music. 5 iv and v give the ‘theme of upflight’ from b. 52–56 plus a triple call (the rising fourth is enharmonically the same as the opening interval of the piece, the first two notes of the ‘theme of dissolution’) and four bars of invocational rhythm reminiscent of the connection-theme. This passage, perhaps the most dramatic, ushers in the recapitulation which, starting pianissimo, is very far from the climactic ones in the Sixth, Seventh and Ninth Sonatas – here is a real drop in tension.

The ‘triple’ principle in the Sonata has been mentioned. To bring together examples of this element: theme 3 is stated twice three times (plus twice more) in the introduction; the two entries of the rising second (ex. 4a) in bars 5 and 13–14 are echoed at the beginning of the Allegro agitato, and the full theme 4, starting with another rising second, follows immediately. At the section marked Tragique there are three falling phrases in b. 92–95 before dissolution sets in. The repetitions of the falling tail of the ‘theme of tragedy’ in the sections marked Tragique. Molto più vivo are, like those of the ‘motive of languor’ in the introduction, twice three and then two more. These set off a section of ‘flight’ each time. Section 4ii is extended to give a triple repetition of the end of theme 4, which sets off the second of the Tragique. Molto più vivo sections.

These triple repetitions, and the high level of repetition of themes and sections in the sonata, help to establish the hypnotic atmosphere of the work which has been mentioned, as do the repetitions on a smaller scale in the Prelude op. 74 no. 2, and the triple repetitions are solemn and ‘magical’ no less than in Mozart’s Magic Flute. The design of the Eighth Sonata, while far from mechanical in its geometry, has reached the highest pitch of symmetry, and as we travel through the symmetries we feel we have lost touch with chronological, linear time, and have entered a realm where, to paraphrase Scriabin, ‘time has been enchanted’. ‘All is always now.’

[1] V. V. Rubtsova, Preface to edition of sonata no. 8. Munich. 2007. G. Henle. p. [III].

[2] Carl Dahlhaus, “Struktur und Expression bei Alexander Skrjabin” (1972). In Carl Dahlhaus: Schönberg und andere, gesammelte Aufsätze über Musik. Mainz, Schott, 1978, p. 231.

[3] Hans Keller, Music, Closed Societies and Football. London, Toccata Press, 1974/86, p. 136–138.

[4] Più, ‘more’, is Skryabin’s marking, glossed in the new Russian complete edition as Più mosso. It is arguable, though, that this marking means the performance should be more intense in all aspects – simply ‘more’.

[5] A. V. Kashperov (compiler, ed. and commentary), A. N. Skryabin. Pis’ma [letters]. Moscow, Muzyka, 1965/2003. Letter no 381, p. 343.

[6] L. L. Sabaneyev, Vospominaniya o Skryabine [Reminiscences of Skryabin] (1925). Moscow, Klassika XXI, 2003, p. 122.

[7] S. E. Pavchinsky, Sonatnaya forma proizvedenii Skryabina [The sonata form of works by Skryabin]. Moscow, Muzyka, 1979, p. 6–7. Gottfried Eberle, “Ich erschaffe dich als vielfältige Einheit”, Alexandr Skrjabin und die Skrjabinisten, Musik-Konzepte 32/33. Munich, 1983, edition text+kritik, p. 43.

[8] E. P. Meskhishvili, Fortepiannie sonaty Skryabina [the piano sonatas of Skryabin]. Moscow, Sovetskii kompozitor, 1981, p.172. Quoted by E. Mikhailov, “Vos’maya sonata A. N. Skryabin: popytka analiza” [Skryabin’s Sonata no. 8: attempt at an analysis], Uchenye zapiski, 8/1. Moscow, Skryabin Museum, 2016, p. 75 n. 14.

[9] Elena Gnesina, Ya privykla zhit’ dolgo… [I am used to living a long time…]. Moscow, Kompozitor, 2008, p. 55.

[10] Kashperov, Pis’ma, letter no. 22, p.68. The ‘middle’ latitudes are between 50 and 60 degrees north and south.

[11] V. Del’son, Fortep’yannye sonaty Skryabina [Skryabin’s piano sonatas]. Moscow, Muzgiz, 1961, p.40–44. Daniel Bosshard, Thematisch-chronologisches Verzeichnis der musikalischen Werke von Alexander Skrjabin. Ardez, Ediziun Trais Giats, 2002, p. 154–159, 162. V. V. Rubtsova, prefaces to editions of sonatas nos. 8–10. Munich, G. Henle, 2007, 2010, 2011.

[12] S. Pavchinsky, “O krupnykh fortepiannykh proizvedeniyakh Skryabina pozdnego perioda” [On Skryabin’s large-scale piano works of the late period] in S. Pavchinsky, ed. and compiler, A. N. Skryabin. Sbornik statei [anthology of articles]. Moscow, Sovetskii kompozitor, 1973, p. 449.

[13] Alfred J. Swan, Scriabin. London. J. Lane The Bodley Head, 1923, p. 106.

[14] V.V. Rubtsova, preface to the Henle edition of Sonata no. 8.

[15] H. P. Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine. Vol. II, Cosmogenesis. London, The Theosophical Publishing Company, 1888, heading to p. 607.

[16] Sabaneyev, Reminiscences, p. 157.

[17] Simon Nicholls and Michael Pushkin, trans., annotated Simon Nicholls, The Notebooks of Alexander Skryabin. New York, Oxford University Press 2018, p. 85.

[18] Op. cit. p. 295.

[19] Cf. “A Note by Boris de Schloezer on the Preliminary Action.” Nicholls and Pushkin, The Notebooks of Alexander Skryabin, p. 47.

[20] H. P. Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine, vol. II, p. 580–581.

[21] Sabaneyev, Reminiscences, p. 162.

[22] Op. cit., p. 263.

[23] Tamara Levaya, “Skryabinskaya ‘formula ekstaza’ vo vremeni i v prostranstve” [Skryabin’s ‘formula for ecstasy’ in time and in space], in A. N. Skryabin: chelovek. khudozhnik. myslitel’ [the person, the artist, the thinker]. Moscow, Skryabin Museum, 1994, p. 101.

[24] ‘Extra-tonal’ is a term used by Russian commentators of Skryabin’s era, Sabaneyev for example, to denote a harmonic style where the tonic is distantly felt as an attraction but resolution is avoided. Stretches of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Kashchei the Deathless (1901-1902) are ‘extra-tonal’.

[25] Sabaneyev, Reminiscences, p. 295.

[26] Cf. E. Mikhailov, op. cit., p.76. He quotes Skryabin: “Harmony and melody are two sides of a single essence”. Mikhailov comments: ‘[…]Has not the embodiment of a specifically Skryabin space-time been revealed here, more exactly, the translation of time into space?’ This brings to mind the words of Gurnemanz to Parsifal during Act One of Wagner’s opera: Zum Raum wird hier die Zeit. [Here time becomes space]. Skryabin’s critical attitude to Parsifal, expressed to Boris de Schloezer, shows that he knew the work. Nicholls and Pushkin, p. 38. Wolzogen’s Leitfaden [thematic guide] to Parsifal was in Skryabin’s personal library.

[27] Мikhailov op. cit., p. 74.

[28] B. Fokht. Filosofiya muzyki A. N. Skryabina [Skryabin’s philosophy of music]. In Skryabin: chelovek. khudozhnik. myslitel [the person. the artist. the thinker] p. 186. Nicholls and Pushkin p.195.

[29] Nicholls and Pushkin, op. cit., p. 106. Notebook of 1905–6.

[30] Hegel: ‘[…] the level and excellency of art, in attaining a realization adequate to its idea, must depend on the grade of inwardness and unity with which Idea and Shape display themselves as fused into one’. Bernard Bosanquet, trans., The Introduction to Hegel’s Philosophy of Fine Art [Aesthetik]. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, 1886, p.138. Skryabin recommended Hegel in a letter to Margarita Morozova, 3/16 April 1904. Kashperov, op. cit., pp. 307–8, letter 322. Nicholls and Pushkin p. 237.

[31] Gottfried Eberle, “‘Ich erschaffe dich als vielfältige Einheit’”. In Aleksander Skrjabin und die Skrjabinisten. Heinz-Klaus Metzger and Rainer Riehn, eds. Musik-Konzepte 32/33. Munich: edition text+kritik, 1983, p. 48–49.

[32] My colleague, the distinguished pianist and professor Dina Parakhina, has remarked that these descending fourths need to be treated always as a release from the tension built in the ascending theme they follow. They need to be played with great lightness and a certain irreality, and are always marked to be pedalled – a super-clear articulation is essential, of course, but this is not the main requirement.

[33] Nicholls and Pushkin, p. 66.

[34] At the basis, however, lies the desire for absolute bliss. Life is upsurge. Nicholls and Pushkin, p. 113, Skryabin’s own footnote in the notebook of 1905–6.

[35] Sabaneyev 1925/2003, p. 295.

[36] “Scriabin’s Symbolist Plot Archetype in the Late Piano Sonatas”, Susanna Garcia,

19th-Century Music, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Spring, 2000), p. 273-300.

[37] Sabaneyev, Reminiscences, p. 162.

[38] Stefanie Hue-Ling Seah, “Alexander Scriabin’s style and musical gestures in the late piano sonatas: Sonata no. 8 as a template towards a paradigm for interpretation and performance.” A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sussex, 2011. p.116. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/6959/1/Seah%2C_Stefanie_Huei-Ling.pdf, accessed 5/10/2016.

[39] V. V. Rubtsova, Aleksandr Nikolaevich Skryabin. Moscow, Muzyka, 1989, p. 223.

[40] The word ‘immediately’ suggests to the present writer that the diminuendo made by many players in the repeated falling phrases, not marked by Skryabin, is not appropriate here: the transition to ‘dissolution’ should be startling and instantaneous – a breaking-through into a different mode of existence.

[41] Nicholls and Pushkin, p.145.

[42] V. Del’son, Skryabin. Ocherki zhizni i tvorchestva [outlines of life and creative work]. Moscow, 1971, Muzyka, p. 322.

[43] Pavchinsky, “On Skryabin’s large-scale piano works”, p. 449.

[44] E. Gunst. A. N. Skryabin i ego tvorchestvo [Skryabin and his creative work]. Moscow, 1915, Jurgenson, p. 32.

[45] Skryabin considered the emergence of consciousness to have a profound effect on the material of the Cosmos. Nicholls and Pushkin, p.107–108.

[46] Op. cit., p. 158.

[47] Both these manuscript sheets are in the Glinka Museum, Moscow.

[48] Sabaneyev, Reminiscences, p. 250.

[49] Op. cit. p. 57.

[50] Op. cit. p. 313.

[51] Nicholls and Pushkin, p. 115–125.

[52] Sabaneyev: Skryabin. Moscow, 1916, Skorpion, p. 48.

[53] Nicholls and Pushkin, p.76.

[54] ‘The majority were enthusiastic for Bergson’. Boris Pasternak, Safe Conduct, trans. Beatrice Scott. In: Boris Pasternak, Prose and Poems, ed. Stefan Schimanski, intro. J. M. Cohen. London, Ernest Benn, 1959, p. 32.

[55] Henri Bergson, Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience, chapter II, “De la multiplicité des états de conscience: l’idée de durée”. Paris, Félix Alcan, 1889, p. 76.

[56] E.M. Forster, Aspects of the Novel. London, 1927/1969, Edward Arnold, p. 154.

[57] Paul Badura-Skoda, essay on the Hammerklavier sonata. Paul Badura-Skoda, Jörg Demus, Die Klaviersonaten von Ludwig van Beethoven. Wiesbaden, 1974, F.A. Brockhaus, p.175.

[58] […] the effect of the harmonic progressions characteristic of the later music is always to weaken the relationship between chords which precede and follow, and this is also a temporal matter. Hugh MacDonald, “Skryabin’s Conquest of Time”, Otto Kolleritsch, ed., Alexander Skrjabin, Graz,1980, Universal Edition/Institut für Wertforschung, p. 62.

[59] […]the renunciation of unidirectional striving […] the locking of the “running spiral” into a spherical form […] Tamara Levaya, “Skryabin’s ‘formula for ecstasy’” (present version from the 2005 edition.) Quoted from E. Mikhailov, op. cit., p. 75.

[60] Sabaneyev, Vospominaniya, p. 254.

[61] T. S. Eliot, “Burnt Norton”, Four Quartets, London, 1944, Faber & Faber, p. 12.

[62] Pavchinsky, The Sonata Form, p. 198–206.

[63] Manfred Kelkel, Alexandre Scriabine: sa vie, l’ésotérisme et le langage musical dans son œuvre. Paris, 1978/1984, Librairie Honoré Champion, livre III p. 146–150.

[64] Kelkel, op. cit., livre III p. 150.

[65] Pavchinsky, op. cit., p. 206.

[66] Pavchinsky does not give bar numbers; they are supplied by the present author.

[67] Pavchinsky, op. cit., p. 204.

[68] G. E. Conus (Konyus) (1862–1933) was a pupil of Arensky and taught Skryabin at an early age. His analytical method, involving the graphic representation of sections of a composition according to bar numbers, was published in the journal Muzykal’naya kul’tura, 1924 no. 1 (“Metro–tektonicheskoe razreshenie problem muzykal’noi formy”) [A metro-tectonic resolution of the problems of musical form] and appeared in book form in the year of his death. The attraction of this method for Kelkel is double: the early teacher/pupil relation between Konyus and Skryabin and the evidence in many manuscripts of Skryabin’s calculations involving bar numbers. The bar numbers of Kelkel’s analysis, in which he counts the number of bars in each section, are supplied by the present writer. Kelkel takes the development as starting with what I have called the ‘cadence- or connecting theme’ at b.118, apparently for reasons of mathematical proportion.